The Three Principal Aspects of the Dharma Path

Now, let's go back to today's topic. Although we may have discussed these ideas before, we will continue to explore them further. It's possible that there may be differences in our understanding and perspectives, but as we engage in these discussions about Buddhism, let's remain patient with one another.

If we choose to study, contemplate, and practice Buddhism, the question arises of where to begin. With hundreds of thousands of teachings and methods available, it can be challenging to determine what to focus on. Fortunately, Je Tsongkapa, the founding father of the Gelug lineage of Tibetan Buddhism, summarized the Dharma path's stages as the Three Principal Aspects of the Path: Renunciation, Bodhicitta, and Correct View of Emptiness. This means that regardless of the teachings or practices, their ultimate purpose is to realize these three principal aspects.

The First Aspect: Renunciation

Renunciation is the first aspect and consists of two elements: the longing to be free from cyclic existence and the goal of attaining liberation, which is a practitioner's top priority. Thus, the only thing a practitioner wants and needs is Dharma practice that leads to liberation, with other things coming only after that. This criterion can be used to determine whether one has renunciation or not.

Many people today believe that studying and practicing Buddhism is something to do later in life, after accomplishing various worldly goals. However, this is not true renunciation but rather using Buddhism for entertainment, like any other consumable. To attain enlightenment, one must have a strong attitude of renunciation, which is the most fundamental element of the three principal aspects of the path. The lack of this attitude is why many people who receive the pith instruction cannot benefit from it.

In the tradition of Chinese Buddhism, lay practitioners often lack the determination to rid themselves of cyclic existence. This is because they do not acknowledge suffering as a fundamental truth of cyclic existence or see the benefits of liberation from it. This may be due to insufficient study of Buddhist teachings or a relatively easy life without experiencing much bitterness. However, for some people, the bitterness is too much to bear, and they never get a chance to practice. For example, a person with cancer may be too tortured by the disease to practice, and an aging person may no longer have the ability to study, contemplate, or meditate.

Young people face their own unique obstacles as well. Their blood circulates rapidly, their hearts beat strongly, and their muscles are filled with various hormones. They are preoccupied with desires, and their minds are troubled and cannot calm down. Thus, it can be challenging for them to practice and cultivate Renunciation, which is the foundation of liberation and indispensable in Buddhism.

The Second Aspect: Bodhicitta

The second aspect of the Dharma path is Bodhicitta, which entails benefiting all sentient beings unconditionally until they attain Buddhahood. However, this is easier said than done for most of us due to our biases. We tend to favor certain groups while disliking others. Bodhicitta, on the other hand, applies to all sentient beings without exception. It elevates us to benefit even rats and flies by recognizing our responsibility to guide, educate, and provide positive influence to help all beings reach Buddhahood. We must be willing to endure many hardships and sufferings alongside them until they attain enlightenment. Only when we have this unwavering determination can we truly claim to possess Bodhicitta.

The relationship between having a solid mind of Bodhicitta and gaining awakening is highly beneficial, as Bodhicitta helps clear obstacles and accumulate merits. This is crucial for dharma practice, as accumulating merits and eliminating obstacles fuel and sustain the long journey. Obstacles, such as distractions or illness, can hinder the practice and need to be removed. By generating Bodhicitta, practitioners can eliminate obstacles and accumulate merits more easily, making the practice more sustainable.

Furthermore, Bodhicitta brings many merits, such as a sense of joyfulness and a clear understanding of the intrinsic nature of phenomena. When I asked Kenpo Tsutrim Lodro about the relationship between Bodhicitta and awakening, he flipped his hand, indicating that it is as easy as flipping your own hands. Bodhicitta is the best antidote to the egocentric mind, which is the real troublemaker and enemy we need to defeat. By turning our attention from self-centeredness to other-centeredness, we can benefit others unconditionally and gain awakening more easily.

In order to defeat the enemy of the ego, it is crucial to first understand what it is. Here is an example to illustrate this concept: Imagine that both you and I are extremely thirsty, but there is only one cup of water available. What would I do in this situation? If I did not have Bodhicitta, I would simply take the cup and drink the water without considering your needs. This is an example of the ego at work. In contrast, a person who has Bodhicitta would behave differently. They would let others drink first because their code of practice is to prioritize the needs of others above their own. They would not hesitate to make a sacrifice, even if it meant giving up their own life. This mentality is a powerful tool that can knock the ego down.

The egocentric mind is the root of cyclic existence. It leads to selfish behaviors and negative karmas, obscures our ability to mindfully observe our own minds, and causes us to see everything from an egoistic perspective. This delusive perspective creates a world of duality and confines us to it, preventing us from experiencing life fully.

Ego is a complex concept that is not easy to understand, but in simple terms, it can be described as a fixed perception. In the Yogacara school of Buddhism, ego is referred to as Klesha, also known as deluded consciousness. According to Yogacara doctrine, the deluded consciousness obscures the mind and causes it to perceive things as entities with inherent self-nature. This may sound technical and full of Buddhist terminology, so let me simplify it for you. Ego is when the mind habitually perceives things from a single viewpoint without giving it a second thought. In Chan Buddhism, it is called the fixed viewpoint, and it leads us to see things only through our own perspectives. Therefore, Klesha or the deluded consciousness is considered to be the root of the mental consciousness.

Ego is a complex and pervasive phenomenon that can prevent us from seeing things from multiple perspectives. Our tendency to attend only to our own thoughts and feelings can make us angry or disappointed when others do not accept our ideas or undervalue our contributions. When we label others as selfish, we often fail to see our own selfishness. This is because the fixed viewpoint of ego makes it challenging to grasp the nature of egolessness. Bodhicitta, on the other hand, can help eliminate ego.

The Third Aspect: The Correct View of Emptiness

The third aspect of the Three Principal Aspects of the Path is the Correct View of Emptiness, which provides insight into the nature of self and phenomena as empty. This view is a core teaching of the Second Turning of the Wheel of Dharma. By practicing the Correct View of Emptiness, we can also apply the teachings of Luminosity and the Inseparability of Luminosity and Emptiness, which are taught in the Third Turning of the Wheel of Dharma and Dzogchen, respectively. However, in the Three Principal Aspects of the Path, Emptiness is the foundation.

The Three Principal Aspects of the Path offers a practical methodology for lay practitioners in modern times who wish to attain realization quickly without reading extensive Buddhist texts. To begin, we must cultivate Renunciation and Bodhicitta and develop a correct understanding of Emptiness. Once we have established this foundation, we can practice with diligence and devotion to achieve realization within this lifetime.

How to Achieve the Three Aspects

Both the sutric and tantric approaches are available to achieve the three aspects. The sutric methods primarily teach Renunciation and Bodhicitta, while the Madhyamaka tradition of the Sutrayana teaches the Correct View of Emptiness. The Tantrayana tradition offers practices like Mahamudra, Dzogchen, and the practice of Nadi, Prana, and Bindu (channels, qi, and essences) to realize the Correct View of Emptiness.

As previously mentioned, the practice of Nadi, Prana, and Bindu may not be suitable for lay practitioners in modern times. While Mahamudra and Dzogchen are beneficial, we may not currently have the necessary capacity to practice them. What can we do in this situation? We can begin by studying texts on Madhyamaka, Shunyata (Emptiness), and Paramita.

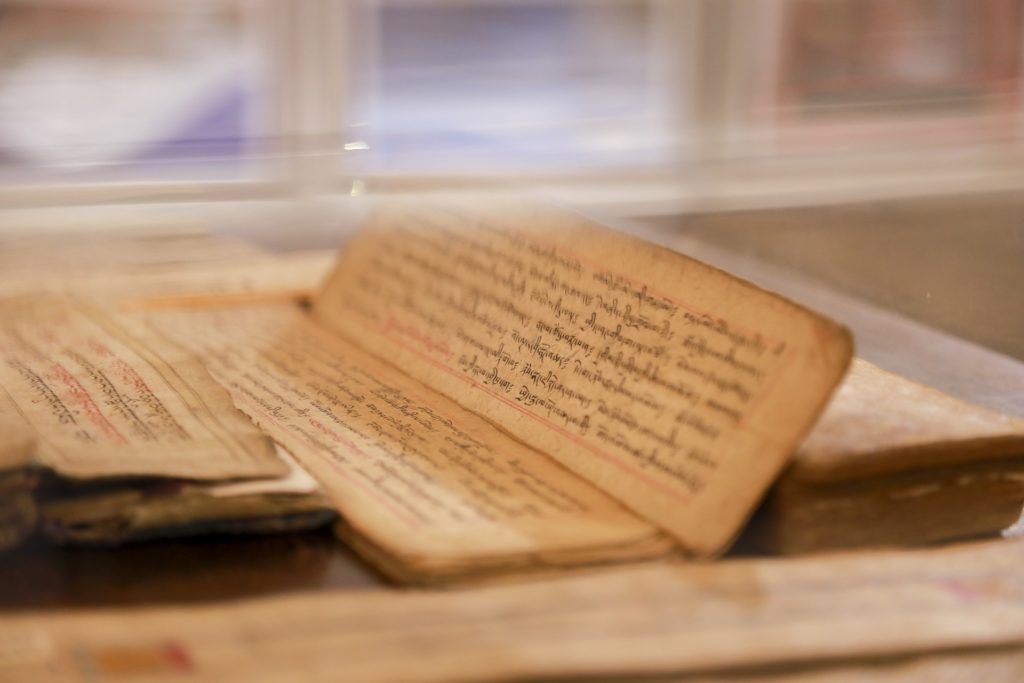

Where can we find theoretical texts on the Three Principal Aspects of the Path? There are many relevant texts available in both Chinese Buddhism and Tibetan Buddhism. A lot of them have been translated into English. However, as our focus today is on Tibetan Buddhism, let us explore the texts on the Three Principal Aspects of the Path that are available in this tradition.

There are several texts available in Tibetan Buddhism that discuss the Three Principal Aspects of the Path, but one of the most well-known is the Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment, also known as Lam Rim Chen Mo. This text, written by Je Tsongkapa when he was 46 years old, provides a detailed explanation of the Three Principal Aspects of the Path. However, Je Tsongkapa later simplified the text as the Middle Length Lam Rim because he thought the Great Treatise was too academic.

Although there are differences between the lineages of Tibetan Buddhism, the majority of them study the Great Treatise. However, some prefer more concise and straightforward texts, such as the commentary on the Three Principal Aspects of the Path found in Luminous Wisdom by Kenpo Tsultrim Lodro. Other masters, such as Kenpo Sodargye and Kenpo Yeshi Phuntsok of the Larong Larong Five Sciences Buddhist Institute, have also written commentary texts on the topic.

Regardless of the text, all texts on the Three Principal Aspects of the Path generally center around how to generate Renunciation and Bodhicitta, accurately grasp the Correct View of Emptiness, and put it into practice. It is recommended to read related texts, such as the Great Treatise, Luminous Wisdom, and Kenpo Sordargye's commentary on Shantideva's Bodhicharyavatara.

In addition to Tibetan Buddhism, there are also texts on the Three Principal Aspects of the Path in Chinese Buddhism. For example, Master Xing'an's An Inspiration to Give Rise to the Bodhi Mind and parts of the Sixth Patriarch's Platform Sutra discuss the importance of giving up worldly attachments and practicing Buddhadharma. However, Je Tsongkapa's Three Principal Aspects of the Path provides a dedicated summary of the three aspects in Chinese Buddhism.

As lay practitioners, if we focus on the three principal aspects of the path, we have the potential to achieve awakening within this lifetime. By cultivating Renunciation and Bodhicitta, we establish a strong foundation that allows us to wholeheartedly study and practice the Correct View of Emptiness. This, in turn, increases our chances of awakening.

The next question naturally arises: how do we achieve awakening? The answer is Madhyamaka. It is the key to awakening and beyond. Firstly, the study and contemplation of Madhyamaka is a shortcut to attaining initial awakening. Secondly, it can serve as a preliminary practice and foundation for effectively receiving the pointing-out instruction in Dzogchen. However, we should be aware that gaining awakening is not an easy task and may take years of dedicated practice. Nevertheless, by continually studying and practicing Madhyamaka, even if we haven't fully experienced awakening, we can still gain an understanding of Mere Emptiness, which is invaluable for a sincere dharma practitioner.

Dedication to the path and the cultivation of Renunciation and Bodhicitta serve as a solid foundation for the pursuit of awakening. Through the study and practice of Correct View of Emptiness, one can increase the chances of achieving awakening in this lifetime. While the journey may be arduous and may take years of dedicated practice, the constant study and practice of Madhyamaka can offer a practitioner an experience of the Mere Emptiness, a valuable experience on the path to awakening.

The Mere Emptiness may not be Emptiness itself, but it serves as a steppingstone towards it. As one's experience of Mere Emptiness deepens, it signifies a higher level of Bodhicitta. If one's guru bestows the pointing-out instruction, awakening may be achieved with just a word or a few words. However, if not, one can continue practicing with diligence and eventually achieve awakening.

Attaining awakening is an exceptional achievement, especially for those practicing Tibetan Buddhism, as it offers the possibility of transcending the cyclic existence forever and attaining Buddhahood in the stage of bardo. In this age of the five corruptions, where human life is limited to about a hundred years, achieving awakening holds significant importance. In contrast, worldly pursuits like accumulating wealth or seeking power pale in comparison.

While it may sound like a fairy tale or superstition to non-Buddhists, the merit accumulated from dharma practice holds immense value to a genuine dharma practitioner. The merit of Buddhadharma is immeasurable and offers the possibility of achieving awakening, the most meaningful pursuit in life. It is crucial to study and practice seriously before drawing any conclusions, as ignorance may be a curse or a bliss depending on one's understanding. A genuine belief stands in stark contrast to superstition, and there is no room for the latter in a practitioner's pursuit of the path.

The Study, Contemplation, and Meditative practice

The study of Madhyamaka is the foundation for our contemplation and meditative practice. We must begin with a thorough study of the texts and commentaries by authentic masters. It is not enough to simply read the texts or listen to teachings; we must investigate the meaning of the words and concepts, ask questions, and seek clarification. We should also compare different commentaries and understand the context in which they were written.

However, we must be cautious not to fall into the trap of intellectualism. Mere knowledge does not lead to awakening; it is the practical application of the knowledge that counts. Therefore, after studying the texts, we must engage in contemplation, using logical reasoning to examine and understand the teachings. We should question our assumptions, challenge our beliefs, and analyze our own experiences.

Finally, we must engage in meditative practice to actualize our understanding. We must cultivate single-pointed concentration and use specific methods to generate insight into the nature of reality. It is only through this process of study, contemplation, and meditative practice that we can gain an experiential understanding of Emptiness and achieve awakening.

However, we must be aware of the pitfalls that can arise during this process. One common pitfall is becoming attached to our own views and opinions, which can hinder our progress. Another is falling into nihilism, rejecting conventional reality altogether. It is essential to have a qualified teacher and a community of practitioners to guide and support us on this path.

Thus, when embarking on the study of the three principal aspects of the path, it is essential to recognize that theoretical study alone is insufficient. Contemplation must accompany it, for it helps eliminate logical impurities and restore mental clarity, which is crucial in meditative practice.

In Tibetan Buddhism, Renunciation is generated through the Four Mind Converters, namely the Difficulty of Finding the Freedoms and Advantages, the Impermanence of Life, the Law of Cause and Effect, and the Defects of Samsara. To deepen our understanding of Renunciation, we can refer to texts such as A Guide to the Preliminaries from the Nyingma Lineage and Kenpo Tsultrim Lodro's Luminous Wisdom. These texts provide reasoning and practical methods for cultivating Renunciation.

However, studying these texts theoretically without contemplation and meditative practice can lead to a shallow understanding of the teachings, making them seem repetitive and dull. Without internalization, knowledge remains on a conceptual level, which quickly fades away. Therefore, it is crucial to engage in contemplation and meditative practice to deepen our understanding and internalize the teachings.

As the Confucian philosopher Yangming Wang once said, true knowledge is about aligning our actions with our words. Knowledge is not just conceptual; it must be embodied through action. When our actions are in harmony with our understanding, knowledge becomes a guide for action. This integration of knowledge and action leads to authenticity and integrity in our words and deeds.

The irony is that many people do not practice what they preach. They say they want to escape Samsara, but their actions reveal that they are attached to it. When they see something they desire, like a beautiful person or wealth, they cannot resist it, despite what they say. The challenge lies in aligning our knowledge and actions. This is especially true when it comes to generating Bodhicitta. We often romanticize the idea of benefiting all sentient beings and becoming a Buddha. However, when it comes to our day-to-day interactions with others, we may fail to live up to these ideals. We may even act unkindly towards those who oppose us. This is a clear indication that we are not living in accordance with our beliefs.

Truly understanding the essence of Shunyata is not as simple as it may seem. According to Buddhist logico-epistemology, there are three aspects to truly understanding something: the name, the reason, and the direct experience. In the case of Shunyata, the name is the term itself, the reason is the theory that explains Shunyata, and the direct experience is gained through contemplation and meditative practice.

Many people can recite the term Inseparability of Luminosity and Emptiness and explain the theory behind Shunyata very well, but unfortunately, they have never directly experienced it through contemplation and meditation. This is a clear example of the separation between knowledge and action. Therefore, we need to approach the three principal aspects of the path with an all-around perspective, treating study, contemplation, and meditative practice equally. Emphasizing one aspect over the others is unwise.

Initially, we study the texts and contemplate their meaning with discipline, developing the foundation for cultivating the mind of renunciation and Bodhicitta. The cultivation of renunciation and Bodhicitta should be integrated into both meditation and post-meditation sessions. After finishing our meditation practice, we must bring the practice of renunciation and Bodhicitta into our daily life, minimizing the gap between the two sessions until they eventually become one.

There is an interesting aspect of the mind that we should be aware of. The concept can influence our minds to some extent, but it cannot truly change our beliefs. For instance, if we repeatedly tell a little boy that his mother is a bad person, his mind may eventually start to believe it. However, once he grows up and sees his mother again, this concept will collapse instantly because blood is thicker than water. Thus, we must not let our minds be fooled by concepts. We must contemplate with critical questions in mind to truly believe in what we are studying.

To do this, we must ask ourselves questions such as why we need to give up worldly pursuits, whether Samsara is really as bad as it seems, whether there is really a hell as the Buddha spoke of, and whether there really are six realms in Samsara. If we want our minds to truly believe in these concepts, we must study Madhyamaka and Cittamatra.

For Chinese practitioners who aspire to develop Renunciation and Bodhicitta, merely reading the Guidance Manual for the Preliminaries of Dzogchen is insufficient. This is because our modern education, which emphasizes scientific reasoning and evidence-based thinking, demands that we have a clear understanding of the reasons behind our beliefs. Therefore, in order to comprehend why Samsara exists, we must study Madhyamaka and Cittamatra thoroughly and contemplate their teachings deeply. This will enable us to truly believe in the existence of Samsara and develop a genuine aspiration to free ourselves and others from its endless cycle of suffering.

Believing in the existence of Samsara is the starting point from which we can understand why Renunciation is one of the three essential aspects of liberation. Without it, the goal of freeing ourselves from Samsara and achieving liberation is merely a daydream. Once we have a strong sense of wanting to liberate ourselves from Samsara, it is time to generate Bodhicitta, which is the stepping-stone of Mahayana. Bodhicitta gives us a heart filled with immeasurable love and courage to unconditionally benefit all sentient beings with equanimity. A person with Bodhicitta is called a Bodhisattva, whose sole purpose is to work towards the liberation of all sentient beings until they achieve Buddhahood. The path that leads to accomplishing the great cause of liberating all sentient beings is called the path of Bodhicitta, which is synonymous with "seeing the true nature of our mind." To see it, we need to make our mind gentle and open, and Bodhicitta helps to tame our monkey mind by putting a leash on all forms of selfishness, discursive thoughts, and negative emotions. The gentler and more open our mind is, the better chance we have of seeing the true nature of our mind stream.

The mind-stream refers to the continuum of Alayavijnana, the storehouse consciousness, or it can be seen as the continuum of the body and mind. Buddhism does not believe that the body has its own inherent existence, but rather that it is a manifestation of the mind that is constantly changing like a stream. Hence, it is called the mind-stream. The Chinese term for the mind-stream, Xiang Xu, is brilliantly precise.

To efficiently develop Renunciation and Bodhicitta, we need to go beyond basic studies. Some intellectuals approach Buddhism thoughtfully, and their approach is highly recommended. They do not blindly accept what has been said about Buddhism; instead, they question the credibility of Buddhist doctrine by studying fundamental theories such as Madhyamaka and Cittamatra. Once they are convinced of the authenticity of these theories, they no longer view Buddhism as superstition or a deception set up by Buddha Shakyamuni and his followers. They do not have the intention of trapping us in their deception.

To determine whether Madhyamaka and Cittamatra are true and accurate, we can rationally analyze them. If they are, it means that Samsara can be established and surpassed to reach liberation. However, merely understanding these Buddhist theories on a theoretical, conceptual level without putting them into practice will not lead to meaningful progress in our study and practice of Buddhadharma.

Three Mistakes: Mistake One

Let's discuss some common mistakes that people make while studying and practicing Buddhadharma. The first mistake is studying the theory without putting it into practice. These individuals may not enjoy or know how to practice Buddhadharma. As a result, their understanding of concepts like Bodhicitta and Emptiness may remain solely at the theoretical level. They may simply recite these terms without truly understanding their meaning or significance. In essence, they are merely playing with words without any practical application.

Many people study Buddhadharma and gain a vast understanding of its concepts, but fail to put them into practice. Some of them even hold advanced degrees, yet they become armchair scholars or talkers who doubt or slack. This happens because concepts alone cannot direct the mind. To avoid falling into this trap, we need to contemplate the texts thoroughly and then sit on a meditation cushion to carry out meditative practice. After meditation, we need to continue practicing in our daily life.

To practice in daily life, we should remind ourselves to benefit others and not harm them anytime and anywhere. If we happen to hurt someone, we should immediately recognize that it goes against the principle of Bodhicitta and remind ourselves that it is wrong. By repeating this practice, we can eventually generate true Bodhicitta and avoid having it remain just a concept.

Without taming our minds to be gentle and open, we cannot experience the true taste of a tamed mind or eventually become a Bodhisattva. We will have no chance to reach the path of accumulation, one of the five paths of practicing Buddhadharma: the path of accumulation, the path of joining, the path of seeing, the path of meditation, and the path of no-more-learning. When a practitioner reaches the path of accumulation, they become a true Bodhisattva, whose mind often rests peacefully in the state of Bodhicitta, immersed in its wonderful experience. If we fail to train our minds this way, we cannot realize this experience.

After years of studying Buddhadharma, many people end up disbelieving in it because they fail to integrate what they have learned into their meditative practice and daily life. They approach Buddhadharma with the same mindset as other types of knowledge, mistakenly assuming that what they learn is good enough. However, there is a fundamental difference between Buddhist study and other types of knowledge, and to acquire true knowledge, Buddhist study requires a complete set of learning methods that goes beyond theoretical study to include thorough and all-around practice with contemplation and meditative practice. Unfortunately, many so-called elites, such as those who hold Ph.D, do not realize this, and their Buddhist studies remain stuck in a place where they should not be, which is a pity.

Three Mistakes: Mistake Two

The second mistake is the reverse of the first. Some people only focus on meditation without any study or contemplation because they assume that meditation is the real deal. While there is a term in Buddhism called "the actual practice," it can be misleading in many cases. The actual practice does not require knowledge of many terms and their definitions; instead, it involves persistent meditation. However, the true meaning of the actual practice is to examine and train the mind through effective practice. If this is not the case, it should be called blind practice. Unfortunately, many people blindly practice Buddhadharma, which is not effective.

Many practitioners in our meditation center fall into this category - they are professional practitioners who resemble ordained monks and nuns, with the exception that they do not shave their hair and receive financial support from patrons for their basic needs. Their primary focus is to immerse themselves in meditation day and night, which leads to experiencing joyfulness and clarity within their body and mind. This state of comfort in meditation is known as Joy, while the refreshment and clarity experienced by the body and mind are called Clearness, which may even lead to the development of supernatural abilities. Achieving the high levels of meditation practice, represented by Joy, Clearness, and No Discursive Thoughts, requires the ability to sit on cushions for extended periods without giving rise to any discursive thoughts or even blinking. Some practitioners can even sit for 12 hours straight without blinking. However, many of them tend to get stuck in this comfort zone and fail to progress further in their practice.

All of them do the five preliminaries, as they are the prerequisites for the actual practice of Dzogchen. Although they work really hard for it, when it comes to the reason for them doing so, you would disappointingly find out it is just to make up the numbers. Since they do not study and contemplate, neither do they truly understand what the five preliminaries are made for nor the essence and methodological techniques of carrying it out effectively. For example, what do they need to achieve by taking refugees in the Three Jewels? How do they go about it? Likewise, what is the goal of practicing Vajrasattva? What is the key to it?

All of them perform the five preliminaries, which serve as prerequisites for the actual practice of Dzogchen. Despite working hard on them, it is disappointing to discover that they do so merely to fulfill a requirement. They neither study nor contemplate the purpose of the preliminaries, nor do they truly understand their essence and effective methodology. For instance, what is the aim of taking refuge in the Three Jewels, and how can one achieve it? Similarly, what is the objective of practicing Vajrasattva, and what is the key to success?

People in the first category tend to study Budhadharma without performing the actual practice, and this often makes them arrogant. For instance, during group discussions when discussing terms and theories, they tend to talk excessively, creating an impression that they know everything, but in reality, they are merely reciting words and playing with concepts in their minds.

The people in the second category are even worse. They believe that they are truly practicing, as they meditate very well and have completed the five preliminaries multiple times. Some of them may have even had some basic experience of Mere Emptiness. However, since they do not study the theoretical aspects, they become arrogant and think that they are special and superior to others. They believe that they will become a Buddha in this lifetime, which is not an authentic practice of Buddhism. Nonetheless, practicing the five preliminaries may bring them some merits as it is impossible to say that there are no merits in doing so. Even reciting Amitabha once has its own merit.

Many practitioners strive to achieve awakening or enlightenment in one lifetime, but they must realize that sitting on a cushion to meditate alone is not enough. If a person frequently enters the stages of Joy, Clearness, and No Discursive Thoughts through meditation, it could be a sign that they may easily be reborn in the realm of heaven or the realm of the long-lived god. (If one is often in the state of No Discursive Thoughts, they tend to be reborn in the realm of the long-lived god, which is one of the eight adversities that prevent people from practicing Buddhadharma.) It is a serious issue when study is not involved. Without guidance from study, practice is like a bird without a head.

Three Mistakes: Mistake Three

The third mistake is also very tricky. People in this category both study and practice, but the two are not integrated. They have done a lot of reading, which unfortunately has nothing to do with their practice. They can memorize many concepts, but when they practice, they do so blindly. The theory they learned does not aid their practice, and their practice does not enrich their studies in return.

Theoretically, the study and contemplation of Buddhadharma can greatly assist meditative practice, and meditative practice can also make study and contemplation more refined and complete. Since our group sincerely embraces an integrated approach to Buddhist study, contemplation, and meditative practice, our fellow practitioners do the same. However, the issue for them is that these elements are not integrated in a healthy manner. What they have studied and contemplated is unable to provide guidance for their meditative practice, and what they have practiced meditatively cannot make their studies and contemplation more focused and delicate. What is the cause of this issue? An experienced instructor is lacking. Without the necessary instructions provided by an instructor, practitioners cannot bridge the theory and practice of Buddhadharma alone, which is truly a significant issue.

The Correct Approach

Now, it comes to the question: what is the right approach? Theories we study must interact with what we practice. For instance, when practicing Renunciation and Bodhicitta, we first study texts written on them and then carry out contemplation and meditative practice in alignment with what we learn theoretically. After practice, we check if our minds are changed by what we learned. We do this repeatedly and persistently. Once this virtuous circle is established, everything falls into place; it will be tremulously beneficial to our dharma practice in the long run.

When it comes to the question of the right approach, we must ensure that the theories we study interact with what we practice. For example, when practicing Renunciation and Bodhicitta, we first study texts written on them and then engage in contemplation and meditative practice in alignment with what we have learned theoretically. After practice, we check if our minds have been changed by what we learned. We do this repeatedly and persistently. Once this virtuous circle is established, everything falls into place, and it will be tremendously beneficial to our dharma practice in the long run.

The key to the right approach is knowing the "why" behind the "what." In the case of the practice of Renunciation and Bodhicitta, we need to know why we do it. The only reason we practice it is to have the mind of Renunciation and Bodhicitta. If we evaluate the quality of the practice by quantity, we miss the point and drift further away from where we should be with the practice. As practitioners in modern times, we need to be determined to spend our whole lives practicing Renunciation and Bodhicitta until we reach enlightenment.

The realization of Emptiness stems from the practice of Renunciation and Bodhicitta, so Emptiness includes the two. An awakened practitioner will never attach to the world, and renouncing worldly things for them is a natural thing. Emptiness tears the notion of the existence of self apart, and they will help others like the right hand helps the left. Behind all they do is driven by Emptiness, and they will help others until they become a Buddha. This is what Bodhicitta fundamentally tells any dharma practitioner to do. The process of understanding Emptiness is the process of the realization of Emptiness, which is the correct view.

It is critically necessary to cultivate the mentality of Renunciation and Bodhicitta before awakening. Completing the quantity is not the most important factor when evaluating if the practice is on the right track. We do not look for how many meditation sessions we have finished or what external results we have had. What we really look for is whether we have genuinely cultivated the mentality or not.

We have just talked about the mentality that a practitioner who practices Renunciation and Bodhicitta should cultivate. To cultivate this mentality, the first thing we need to do is study related texts and then contemplate their meanings. The study and contemplation of Madhyamaka and Cittamatra also help us generate true renunciation. Why? Because during studying, contemplating, and meditating on Madhyamaka and Cittamatra, we will find out: "Wow! The nature of the world turns out to be like this." If the mind truly believes it, renunciation will naturally emerge. When we find out the nature of the world, we are bound to have a strong sense of altruism, which gives rise to Bodhicitta. This is just the opposite of what we now habitually cling to. We are only concerned about our own welfare, and every thought we have is driven by it.

Sometimes we do things that benefit others, such as charity or volunteer work, and we may believe this is an act of true altruism. However, according to Buddhism, this is not necessarily the case. A Chinese idiom states, "By offering a rose to a person, the aroma lingers in my hand." The act of offering the rose is merely a means to an end; the end goal is to experience the aroma lingering in one's hand. Similarly, when we say, "I want to be a volunteer because I want to help people," we may believe that our intention is purely to benefit others. However, if we look deeper, we may discover that behind this desire to help is a need to feel good and secure. In other words, the real motive behind our actions may be to benefit ourselves.

True altruism in Buddhism is known as Bodhicitta, a pure attitude of wanting to benefit others unconditionally. The sole purpose of this attitude is to benefit others, without any expectation of reward or benefit for oneself. Although many joyful things may happen to us when we benefit others, these are only byproducts. The fundamental motive behind our actions must be to unconditionally benefit others. This requires consistent effort, including the study and contemplation of Buddhist theories, as well as practice both on the cushions and in our daily lives. Without this level of commitment, it is impossible to achieve awakening, which involves becoming a Bodhisattva, someone whom all sentient beings depend on. A true Bodhisattva will never be selfish, and a selfish "Bodhisattva" cannot be someone whom all sentient beings depend on. It is ridiculous to imagine a "Bodhisattva" who is selfish.

Many practitioners are unable to yield good results in their practices because they lack Renunciation and Bodhicitta on a basic level. Instead, they chase supernatural things and fantasize about becoming superheroes like the Avengers. They admire powerful individuals and desire to become like them. However, this approach is misguided. We need to sincerely investigate whether Buddhist theories and practice methodologies work, rather than relying solely on faith without reasoning. We cannot judge the efficacy of Buddhism based on functionality alone, as exemplified by the fall of Nalanda University.

Sometimes, blind faith or groundless faith may work, but we must consider the context in which it worked. Claiming that blind faith works all the time would be misleading. While there are many fascinating stories and anecdotes in Buddhism, not all of them can withstand close scrutiny, leading to doubts and ultimately abandonment of faith. This could turn everything into either a comedy or tragedy. To approach Buddhadharma safely and effectively, we should start by studying related texts and contemplating what we have learned from them. We can then deepen our understanding through meditative practice, both on the cushion and in daily life.