Someone asks how the reasoning method of "Neither One Nor Many", one of one of the five Madhyamaka reasonings to demolish the notion of inherent existence, can be used to negate the existence of God?

There are only two ways of knowing the universe: inferential knowing or analytical reasoning, and direct knowing or intuitive cognition. God, the creator of the universe, is nowhere to be found through both ways of knowing.

Here, God refers to many different things; for instance, Elementary particles are "the God" of Stephen Hawking. Though in his intuitive cognition, he could not really see elementary particles with his eyes, he concluded, merely based on the data he collected, that the origin of the universe is from the explosion of elementary particles

Have people still alive today directly seen God with their naked eyes? If someone says they have in their dreams, it does not count because we all know that what we perceive in our dreams is not a direct perception by our eyes and other sense organs.

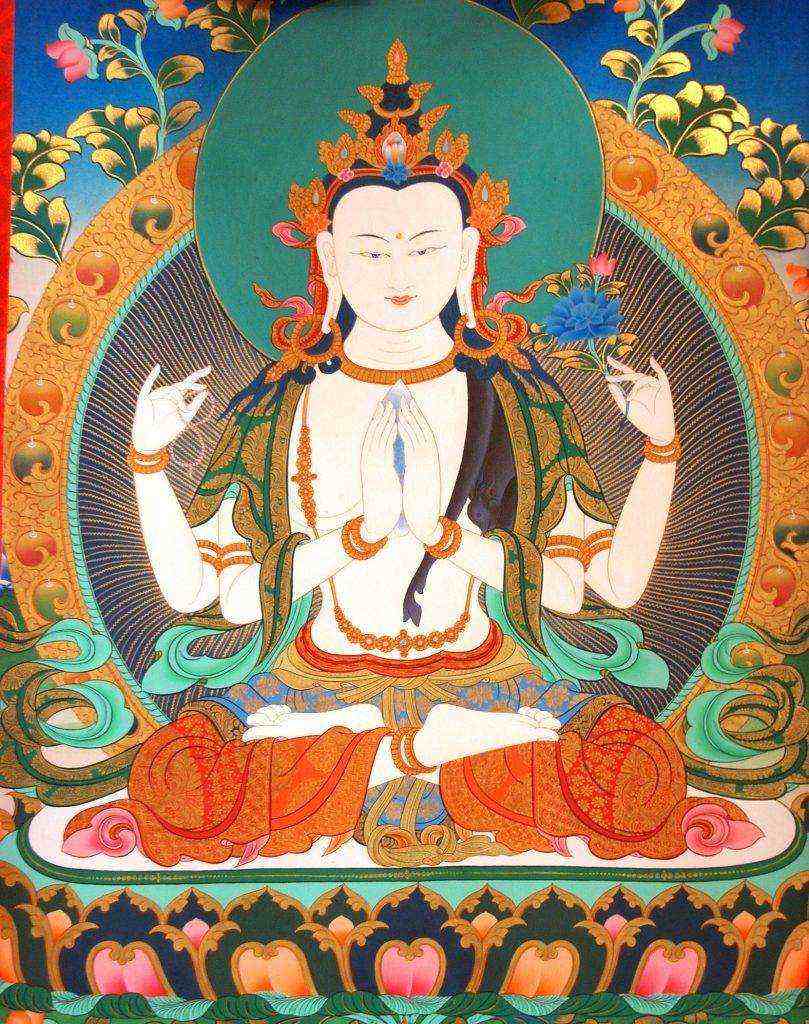

Devoted religious practitioners could see or experience supernatural things; for example, some Christians would claim that they could see unusual things when praying to God with strong devotion, but that is just an illusion in its nature. Many Buddhist practitioners who perform Yidam practice can directly see Yidam. In the Yidam practice, practitioners place a Thangka of the Yidom in front of them and observe it over and over again until the Yidam vividly appears before their naked eyes. Initially, the appearance of the Yidam is somewhat fuzzy, but when the visualization process goes on, the appearance becomes crystal clear. Eventually, one can touch and talk to the Yidam like a real person.

Whatever appears, Yidom or God, the first question we should ask is if he could withstand the tag of the indivisible one.

Neither can. Why? Because they change. Anything that changes cannot withstand the tag of the indivisible one. The appearance and disappearance of Yidom or God depend on the meditative visualization you do. When you do it, they appear. When you stop it, they disappear. How they appear to you also changes by the way you visualize them.

In the case of Yidam practice, if you visualize that there are three buttons on the outfit worn by the Yidam, then he appears with the three buttons on the outfit. How many buttons would appear on the outfit entirely depends on how many of them you visualize. If the appearance of the Yidam and the number of buttons appeared on the outfit are totally independent of your meditative visualization, it would have nothing to do with what and how you do it. Therefore, in the end, you will realize that your mind is the one that makes things appear and disappear. And that is why we say that Buddhist philosophy is true.

God cannot withstand the tag of the indivisible one either, because his appearance and disappearance are also conditioned by many external factors. If one of them changes, he changes, too. If he is "one", he should remain unchanged; therefore, no matter what changes, he should not disappear.

This is very difficult to take in for many of us. We would be confused by a question: Why can't 'one' just disappear? We tend to assume that there is a thing that never changes and hides in somewhere we do not know, waiting for our perception to reveal it. It comes into view the moment we look at it, while it fades away when we do not look at it.

However, cognitive science points out that this kind of thinking is wrong. If the thing we perceive stays unchanged, the perceiver ––– our cognitive mind or consciousnesses, must remain unchanged, too.

To expand more on it, let us take a look at the relationship between eye consciousness as the perceiver and the object as the perceived. We can only be sure that the object perceived by eye consciousness will remain unchanged if eye consciousness itself stays unchanged. This unchanged eye consciousness is a precondition for affirming that the object is unchanged. If this precondition is not met, claiming that the perceived is unchanged becomes invalid.

Likewise, eye consciousness will stay unchanged only if the perceived object is unchanged. If the two are unchanged, the moment before and after will stay unchanged. Only in this way can we be sure that the unchanged object would be perceived by eye consciousness. In this scenario, we would look at the object all the time, and hence it would become an indivisible part of eye consciousness. If eye consciousness and other conditions could stay unchanged, the universe would not exist. That is why the great master Mipam Rinpoche once said that everything in the universe would vanish upon discovering an entity with inherent existence.

This reasoning might sound absurd at first glance, but it is valid when we look at it closely–––if eye consciousness could perceive an unchanged object, it would remain unchanged, too; furthermore, since eye consciousness is originated from Alayavijnana, the base consciousness, if it could remain unchanged, other consciousnesses would remain unchanged, too; therefore, the universe would be stuck in this state forever.

"No, it does not work that way. No sooner than my eyes shift than the object starts changing." You would argue. But, when the very moment you shift your eyes, your entire cognitive mind (the eight consciousnesses) starts changing simultaneously. So, you have nothing else that you can use to approve that the object appeared does not change. You just can't.

For this reason, claiming entities such as God would exist is just a concept fabricated by your cognitive mind. We can't perceive an entity with independent existence. As we said earlier, there are only two ways of knowing things–––inferential knowing and direct knowing. By the reasoning we have done so far, we know that we cannot affirm the existence of God through inferential knowing, and neither can we directly see him. The point is that we cannot see God either way.

"What if the inner spirit of God remains unchanged? And is his external appearance the only thing that changes?" You would ask.

In Christianity, different narrations depict different appearances of God. For example, the appearance of God in the Sistine Chapel ceiling is an old man with a grey beard. In the Bible, it is said that "God formed a man from the dust of the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living being." "So, God created man in his own image. In the image of God he created them; male and female he created them." "God then called the man Adam, and later created Eve from Adam's rib."

Suppose the appearance of God really is an old man, and his inner spirit remains unchanged; then there is a question we all need to answer: Is the relationship between the external appearance and immutable inner spirit of God the same or different?

Let us say they are the same. In this case, when the external appearance changes, the spirit changes accordingly. Therefore, God cannot stand up for the tag of "one". On the other hand, if they are different, is God the external appearance or the inner spirit? To tackle this question, someone was trying to abandon the idea of depicting God as an old man or so. Instead, he was trying to find an immutable objective spirit known as God.

If the objective spirit is absolutely unchanged, how does it work? How does it interact with our individual spirits? How can we find it? The moment it works, it changes; therefore, the so-called objective spirit cannot withstand the tag of "one" either.

"God has the supernatural power to manifest himself in various forms," someone argued online. Let us negate this notion. When talking about whether the essence and manifestation of God are the same thing or two different things, we cannot simply say they are "neither the same nor different" because it is just a word.

Someone else said, "God did not say he's one, so he's everything." Of course, no believers would say that God is "one", but to justify the existence of God, he must be one ––– the immutable one. To say God is everything, you must validate it because it is not what you say it is. Logically speaking, when negating, if people who hold the view that God has an inherent existence accept that God is not one, the inherent nature of God's existence becomes invalid. Although nobody would say that I exist inherently, we tend to attach to the notion of "I" which exists inherently. The negation of the existence of the objective spirit is to place the attachment that we have towards the notion of the inherently existing "I" under our investigation. In doing so, we will find out that the thing we attached to, if it really exists, must withstand the tag of "one".

If the relationship between God and his manifestation is like the one between the mind and phenomena arising upon the mind, God becomes the mind. Therefore, whoever accepts it becomes a Buddhist.

Buddhism states that the mind changes as well, so it does not stand up for the tag of "one"; this is exactly why it transforms. This is how Buddhism views the universe. If there is an inherent "one" out there independent of the mind, no matter if it is the spirit or matter, as long as it remains unchanged, there is no way that it could interact with us at all. Logically and cognitively, it does not make any sense.

Saying God has the power to transform means movement engaged in whatever he does. For example, God thought: "I am going to create a man called Adam." This thought indicates he moves. In other words, he thinks, therefore he moves. Let us take this analysis further. Transformation is an illusion in its nature. Therefore, is this illusionary transformation created by the creator performing a transformative function? Or is it independent of the creator? Is there an external source, such as energy, to bring forth the transformation?

If the creator and the transformative power are the same, the transformative power must remain unchanged since the creator remains unchanged; hence there is no transformation occurring. Conversely, if they are two different things, the creator will be unable to control transformative power, which is a big problem.

From the Buddhist viewpoint, what is the relationship between the subjective mind and its function? Let us again take eye consciousness as an example to explain. If the mind could stand up for the tag of "one", it would never bring forth eye consciousness. Therefore, Buddhism states that as the mind is not "one" either, and the subjective mind is everything, it cannot be regarded as the immutable one. However, this problem can be solved by Emptiness, the correct view that reveals the truth ––– there is no such thing called the subjective mind.

That “no subject” does not mean the cessation of cognition; in other words, there is nothing at all. When perceiving something, if you say that you perceive nothing, which is complete nonsense. No one can find a thing that is called nothingness, if which, let us say, could be found, then this thing called "nothingness" would need to withstand the tag of "one"; however, it cannot by all means.

Likewise, since the subjective mind is nowhere to find and cannot withstand the tag of "one", it is able to transform ––– Emptiness is Form. This is why Madhyamaka strongly opposes the notion of inherent existence and makes every endeavor to demolish it.

Buddhism states that whether the universe is made of matter or arisen from the mind, it cannot withstand the tag of "one", which is the core idea of the reasoning method of "Neither One Nor Many", aiming to completely demolish the notion of inherent existence. Once the notion of regarding the external matter as "one" is destroyed, the notion that God exists externally is also destroyed. Only with this realization will we be aspired to relentlessly undertake the quest of searching for where all fancy phenomena, if not made of matter nor created by God, originate from. Therefore, demolishing the notion of inherent existence we take for granted is the cornerstone upon which the Buddhist worldview will be truly established.

Extracted from and edited based on Chapter 3 of The Teaching of the Seven Points of Mind Training.